Why India’s Elite Are Betting Big on Defence

The Billionaires Are Building the War Room

Two weeks ago, during a breakfast meeting with a retired General-turned-VC investor, I asked him something that’s been on my mind:

“How did India’s defence sector go from sluggish to soaring in less than a decade?”

He smiled and said, “Simple. Defence is an investment thesis.”

What did he mean by that?

It sent me into a flashback. Not too long ago, India’s defence sector looked like a stitched-up patchwork of foreign parts and forgotten ambitions.

We had gained independence, but not autonomy.

Soon after achieving independence in 1947, India inherited outdated British military equipment, lacking a domestic arms industry.

Efforts to build self-reliance began under Nehru in the 1950s, with defence production limited to the public sector and the creation of DRDO. From the 1960s to 1980s, India’s defence sector was led by public-sector units like HAL, BEL, and Ordnance Factories. They developed indigenous projects like the HF-24 Marut fighter, Vijayanta tank, and missile programs.

But despite heavy investment, nearly 70% of key defence equipment was still being imported.

In 1987, one scandal cast a long and chilling shadow: Bofors.

The Bofors scandal was a defense corruption case involving a ₹1,437 crore (that’s about ₹22,000 crores in 2025) deal for Swedish howitzer guns. It alleged that bribes of ₹64 crore in illegal kickbacks were allegedly paid by Swedish firm Bofors to Indian politicians and middlemen to secure a defense contract.

These payments violated government rules by involving non-transparent offshore accounts and led to eroded trust in then-Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and contributed to Congress' defeat in the 1989 general elections.

The aftermath:

The Bofors scandal created distrust in foreign arms deals, leading to delays and stricter scrutiny in defense procurement.

It sparked early calls for indigenous defense manufacturing to reduce dependency on imports. Later inspiring policies like “Make in India – Defence” and Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) and strengthening the argument for DRDO and public sector units (like HAL, BEL) to take the lead in defense production.

The controversy influenced long-term policy shifts toward self-reliance, eventually shaping initiatives like Make in India Defence.

Then came the Kargil War in 1999 where India emerged victorious, while the cracks were impossible to ignore.

The war exposed some harsh truth- our forces faced critical gear shortages, procurement delays, and a system too slow to keep pace with modern warfare. Kargil became a turning point, forcing India to confront the cost of its policy inertia and rethink its approach to defence modernisation.

Defence budgets, then, were increased, modernisation picked up pace, and private players like Tata, L&T, and Mahindra were allowed to enter defence manufacturing. Key projects like BrahMos with Russia and imports like Su-30 jets filled capability gaps. Meanwhile, DRDO, HAL, and the Navy advanced indigenisation with Agni missiles, Tejas, and warship projects.

DRDO and HAL marked some key milestones in the Indian history- the Agni missile series became operational, and the Tejas fighter jet took its first flight.

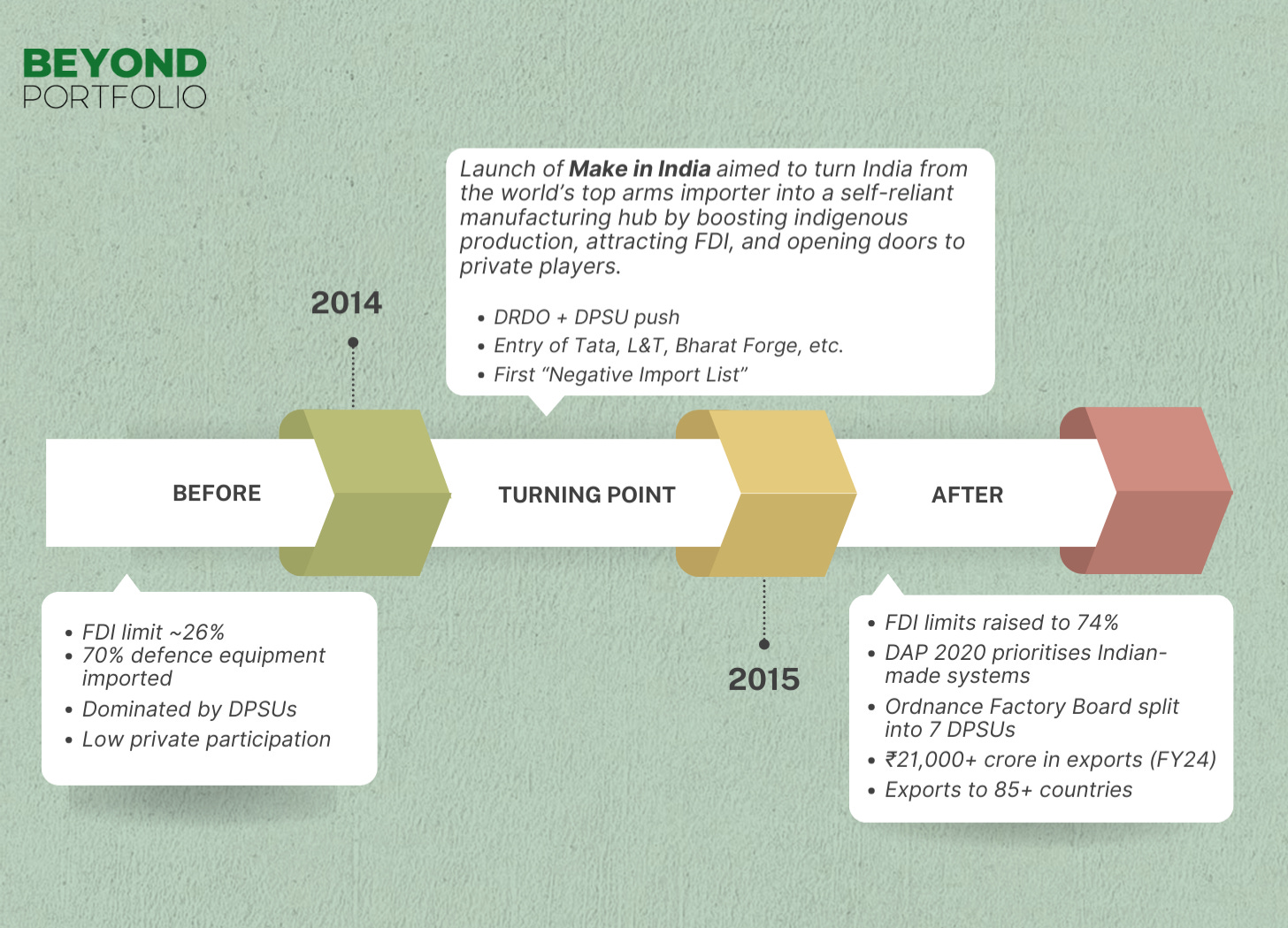

In 2014, “Make in India” gave a strong push to domestic defence manufacturing, later amplified by Atmanirbhar Bharat. The vision, this time, was clear: India shouldn’t just make in India- it should also invent here.

Programs like iDEX started encouraging startups and small companies to build new solutions together with the armed forces. The message was clear: India shouldn’t just make in India- it should also invent here.

To push this vision forward, the government relaxed FDI rules, raising the limit to 49%, and later to 74% without needing special approval. This attracted global defence giants like Lockheed Martin and Kalashnikov to set up joint ventures in India.

The defence buying process was also revamped through the Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) 2020, which gave priority to systems designed and developed in India. Startups and private companies, once left out, could now access funding and win defence contracts that were earlier reserved for public sector giants.

In 2021, the Ordnance Factory Board was split into seven new companies. These new defence public sector units (DPSUs) soon became profitable, and started chasing export deals.

Result? India’s defence exports have skyrocketed from just ₹686 crore in FY14 to over ₹21,000 crore in FY24. That’s a 30 fold increase in just 10 years! The country now exports a wide range of products, including BrahMos missiles, artillery systems, radars, and patrol boats, to more than 85 countries.

US, Southeast Asia, Africa now source components and sub-systems from Indian firms. But why countries like the Philippines will choose Indian over French?

French defence exports, like the Rafale, are world-class but they come with a world-class price tag too. For nations like the Philippines, facing real security threats but operating on tight budgets, high-end Western systems are often out of reach.

That’s where India steps in. A Tejas fighter or Akash missile isn’t just more affordable, it’s built to flex. India offers customization for local climates, terrain, and strategic needs, something Western manufacturers often overlook.

This is India’s edge: cost-effective combat-ready systems. We’ve cracked this model before in sectors like mining and coffee.

And now, defence is set to be next.

Then came Operation Sindoor in June 2025, where India launched a precision military strike in response to cross-border aggression from Pakistan.

What stood out wasn't just the success of the mission but the fact that it was executed using Indian-made weapons and defence systems. From missiles to surveillance tech, the operation showcased how far India’s indigenous capabilities had come. As a result, more nations are now showing interest in buying defence products from India.

During the operation, Indian-made weapons and equipment were used effectively, and this has impressed other countries. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh had asserted in 2024 that this is a big opportunity for Indian defence companies because global military spending has gone over 2.7 trillion dollars.

He explained that in today’s uncertain world, assuming peace will last forever is risky. Conflicts can break out without warning, and countries that are unprepared often pay a heavy price.

And history has indeed shown that the real work of strengthening a nation’s defence must happen during peacetime.

Now that we’ve tracked India’s defence story from post-Independence to Operation Sindoor, let’s discuss some defining truths about this sector.

Entry Barriers Are Brutal

Defence is not your average manufacturing industry. It demands massive upfront capital, deep R&D muscle, years of trust-building, and clearances at the highest level. You can’t bootstrap your way into this space.Deals Run in Thousands of Crores

Whether it’s a warship, a fighter jet, or a surveillance system- everything is built for national security, not shelf sales. The size, complexity, and timelines of these projects require firms to think in decades, not quarters.Privatisation is Picking Up Pace

What was once the exclusive turf of DPSUs is now opening up. Private firms are not just participating, they’re winning contracts, exporting systems, and co-developing defence tools.FDI Is No Longer a Bottleneck

The government liberalised defence FDI to 74% under the automatic route and up to 100% with approval. That change quietly enabled global giants to partner with Indian firms and bring in capital, IP, and credibility.The Bureaucracy is Evolving Too

With clearer procurement rules (DAP 2020), faster licensing, and a push to streamline approvals, the old red tape is giving way to a more agile ecosystem.And this is exactly why India’s elite are now betting big on defence.

The Russia–Ukraine war proved how 21st-century battles are fought with drones, satellite intel, and hybrid warfare tactics. The Israel–Hamas conflict reaffirmed the need for multi-layered missile defence systems and AI-powered surveillance. Tensions in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait have forced the U.S. and China into an arms race of influence.

India, too, cannot afford to lag. With two hostile neighbours and growing geopolitical ambition, it needs both indigenous capability and industrial muscle. That’s why defence is becoming a high-stakes, high-prestige investment.

This is the bet India’s elite are making, not just on weapons, but on national leverage. For them, it’s also about influence, scale, and being on the right side of history.

India is going to no 1 country in defence