India–US: Tariffs Down, Stocks Up. Separating Sentiment From Earnings

The US removed the 25% penal tariff and reduced the reciprocal tariff from 25% to 18%, effective February 7, 2026. That puts India broadly in line with Asian peers on tariff rates of 15 to 19%.

The deal structure: what actually changed

Following the successful conclusion of the interim agreement, tariffs will be eliminated entirely for generic pharmaceuticals, gems and diamonds, and certain aircraft parts. India also receives a preferential tariff-rate quota for automotive components and exemptions under Section 232 for aircraft parts.

India, in return, committed to eliminate or reduce tariffs on all US industrial goods and a wide range of food and agricultural products, including dried distillers’ grains, red sorghum, tree nuts, fresh and processed fruit, soybean oil, wine, and spirits. India also committed to purchase $500 billion in US goods over five years, including energy, aircraft, technology products (GPUs and data center equipment), precious metals, and coking coal, and pledged to halt Russian oil purchases.

Both countries also agreed to strengthen economic security alignment, address non-market policies of third parties (read: China), and cooperate on investment reviews and export controls.

A useful way to read this structure is simple. India gets tariff relief and some zero-duty corridors where US industry also benefits. The US gets a committed, expanding destination market for strategic sectors, plus a strong signal on energy alignment. That does not make the deal “bad.” It does mean the power balance is visible in the terms.

Why markets moved: sentiment is rational, but incomplete

The initial rally makes sense. Tariff compression from 50% to 18% is a 32-percentage-point relief, which improves competitiveness for Indian exporters in the US market. For sectors hit hardest by the tariff spike in 2025, the relief is immediate and material.

But sentiment-driven rallies compress nuance.

First, tariff relief is not the same thing as demand creation. It improves your position in the race. It does not guarantee you win orders.

Second, the benefits are uneven. Zero-duty lanes help a few high-value export categories. A large share of India’s labor-intensive exports still face an 18% wall.

Third, the costs of the deal are not captured in exporter P&Ls. They sit elsewhere. In what India imports more of, in which domestic sectors face new competition, and in the policy constraints embedded in conditionality.

Who wins structurally: the direct beneficiaries

Pharmaceuticals (generics)

Zero tariffs on generic pharmaceuticals is the cleanest structural win. The tariff relief directly improves competitiveness in a price-sensitive market where cost shocks are hard to pass on.

What to watch is not the headline. It is the earnings split. Does the benefit show up in realizations and margins, or does competition compete it away through price cuts?

Gems, jewellery, and diamonds

Zero tariffs on gems and diamonds benefits exporters in a concentrated, high-value category. India’s edge is scale and specialization, and tariff elimination protects that edge.

This is also one of the categories where the US has less domestic supply interest, which makes the relief feel more like genuine trade complementarity than pure bargaining.

Textiles, leather, and chemicals

These sectors benefit immediately from moving to 18%. That matters, because they compete on thin margins. But this is where the “win” narrative needs restraint. 18% is survivable. It is not free access.

In labor-intensive exports, the difference between “competitive” and “booming” is small. A stronger rupee, a softer US consumer, or a competitor negotiating similar terms can erase the edge quickly.

Automotive components (preferential quota)

A preferential tariff-rate quota improves access for suppliers already qualified in US supply chains. This is a real opportunity, but it is quota-shaped, execution-heavy, and slow-moving.

The long-term upside is not a one-quarter margin pop. It is supplier qualification and repeat contracts.

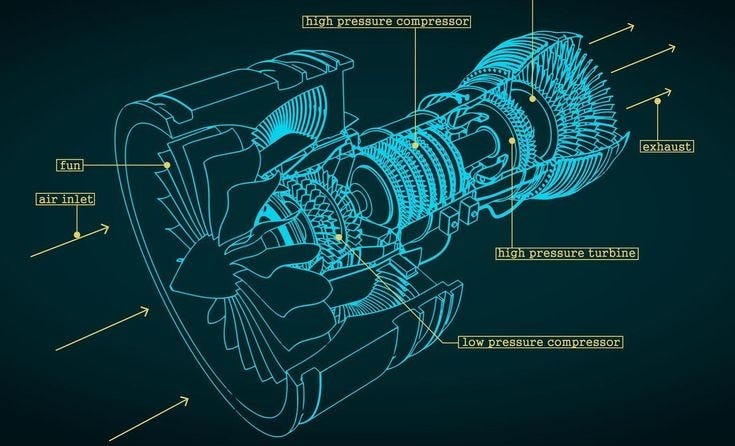

Aircraft parts and aerospace

Exemptions under Section 232 for aircraft parts matter because aerospace is a long-cycle business. The compounding happens when suppliers get embedded into multi-year programs.

This is also a reminder of the deal’s logic. Where US industrial priorities benefit, market access is easier to grant.

Who benefits indirectly: the second-order winners

IT services and technology exports

The direct tariff impact is limited because IT services are not goods. The indirect impact is strategic. Better alignment and greater tech trade can improve the operating environment for India’s tech ecosystem, especially where access to advanced compute is a constraint.

The nuance is that this “access” may come bundled with tighter alignment expectations. That is good for certainty. It may be less good for optionality.

Domestic steel, cement, and infrastructure

The $500 billion purchase commitment implies higher imports of energy, coking coal, and aircraft. Whether that helps India depends on two things: the price at which these imports land, and whether they replace existing flows or add to them.

If replacement, the economic impact is muted. If incremental and more expensive, it can flow into inflation, input costs, and current account dynamics.

Logistics, ports, and trade enablers

If export volumes rise structurally, logistics benefits. But this is lagged. You will see it after you see sustained order wins, not after a one-week rally.

What the market is underpricing: the constraints and trade-offs

India’s own tariff cuts on US goods

India’s commitment to reduce or eliminate duties on US industrial goods and a wide set of agricultural items creates domestic competitive pressure. The pushback here may not show up as headlines, but it can show up as delays, exemptions, or non-tariff barriers. Watch implementation, not announcements.

The $500 billion purchase commitment: optics versus execution

Annualized, $100 billion per year is large. The key question is whether it is incremental or repackaged baseline trade.

Even if it is repackaged, it signals something important. India is positioning itself as a large, reliable destination for US industry. That attracts goodwill and reduces uncertainty. But it also deepens dependence.

Energy conditionality as a policy constraint

The penalty tariff’s linkage to Russian oil purchases introduces a different kind of leverage. It is not just about tariffs. It is about monitoring and re-imposition risk. That may reduce India’s room to optimize energy sourcing purely on price, which has second-order effects on inflation and fiscal math.

This is not a moral judgment. It is a mechanical one. Conditionality changes the range of choices.

Rupee appreciation risk

If sentiment and flows strengthen the rupee, exporters lose part of the tariff relief through FX. A 3 to 5% rupee move can be enough to materially dilute the benefit in low-margin categories.

Execution and follow-through

The agreement is a framework, with formal signing expected in March 2026, and the broader BTA still under negotiation. The risk is not reversal tomorrow. The risk is that this becomes the baseline, and future negotiations start from a place where India has already conceded meaningful ground.

What to watch next quarter: the earnings transmission test

If you want to know whether this deal is creating earnings, watch for these signals:

Export realization commentary: Did pricing or realizations improve in the US, or did volumes rise only with price givebacks?

Order book and inquiry trends: Especially in auto components, aerospace, and industrial supply chains.

Market share gains: Evidence that India is taking share from Vietnam, Bangladesh, or China, not just recovering from a tariff shock.

Input cost effects: If energy and coking coal sourcing shifts, what happens to landed costs and pass-through?

Policy follow-through: On India’s tariff cuts, look for timelines, exceptions, and sector-level resistance.

Currency: If INR strengthens, interpret exporter commentary through that lens.

The bottom line: relief is real, but leverage is visible

This deal removes a tariff wall that was actively damaging exporters. That matters, and the market is right to respond.

But the deeper read is more uncomfortable. India did not negotiate from a position of equal leverage. It negotiated from a position of needing access to the richest market, and needing critical technologies. That does not make the outcome “wrong.” It does mean India may have paid more than the headlines suggest, and the costs may show up outside the export P&L.

Sentiment moved fast. Earnings will move slowly. And the real scorecard will not be the index reaction. It will be the next two quarters of export realizations, and the next two years of how much policy flexibility India quietly gave up for certainty.